Go to navigation for Accessible Tests Resource Center

Orbit Reader 20 Explained

By Larry Skutchan

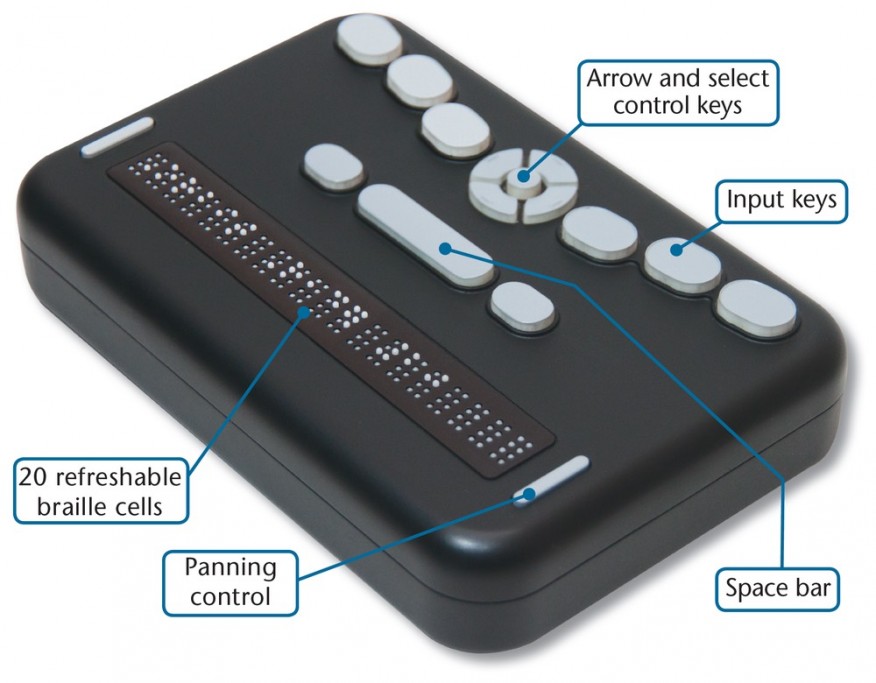

The recent announcement at CSUN (March, 2016) about the new refreshable braille display with SD card and stand-alone functionality deserves some additional information.

In brief, it combines simplicity, essential functionality, and connectivity in a unique and low priced package to make reading braille more practical in a number of situations.

With the fast pace of mobile technology development, smart phone capabilities continue to increase and prices fall. In an ideal world, these handsets would include screens that morphed into braille characters or tactile representations of images available at any time, just like the normal touch screen. There is no doubt that day is coming, what we do not know is how far away it is. Most agree probably not within the next five or even ten years. In the meantime, blind mobile technology users continue access through increasingly better speech output accessibility, but braille is nearly always achieved by employing an external device, much like a Bluetooth keyboard, except in this case, the peripheral is a refreshable braille display sometimes even with a braille keyboard from which the user may type and control the phone. This works, but few can argue that one single unit that included the braille components is far superior. Here, the ugly truth in the field of manufacturing products for a low incidence population arises—no big for-profit manufactuer can justify the expense verses return. That is one reason the field fortunately includes a number of specialized companies with expertise in hardware and software that design products that include braille. Over the years, their electronic braille products organized into three categories: Braille Terminal, Note Taker, and PDA.

Three Categories of Devices

One problem that makes these devices so difficult to discuss is the lack of consistent terminology for an admittedly confusing set of capabilities, so while these terms sound archine and computer speak, let’s use them for the sake of clarity.

The braille terminal is a device that connects to a host and contains no other functionality. It usually includes a USB and Bluetooth interface and sometimes features a braille keyboard.

The PDA describes a note taker that uses a mobile operating system to provide all the services of a modern smartphone or tablet. Modern PDAs include Android and Windows implementations. Of course, this is the obvious next best solution to the user desiring the ultimate experience. The problem is cost. While one can obtain a well-equipped iPhone for around $800, these devices cost thousands, and while it is almost palatable to spend $800 every three years or so to upgrade to the latest, spending that much to keep up hurts lots more.

The note taker works like a braille terminal, but it includes additional functionality like note taking or calculator. These devices always include a braille keyboard.

The note taker offers a middle ground approach. It provides minimal essential functionality in its stand-alone operation, and lets the user connect to a host device for more demanding tasks like web browsing or Skype calls. The disadvantage is the inconvenience of having two separate devices to contend with, but this aspect becomes an advantage when it is time to upgrade to the next generation of phone or tablet.

The other disadvantage of connecting to a host is the danger of losing the connection when you need it most. While advances in Bluetooth technology have largely eliminated this problem, one must be aware that it could happen. This is where the essential stand-alone functionality comes in. When everything runs on the same device, it is a pretty good bet it will be available in nearly any circumstance.

Orbit Reader is designed as a note taker

Its stand-alone capabilities include reading, writing, and file management. For anything else, one must connect to a host device that provides those services. In this usage model, the Orbit Reader becomes a terminal that shows the braille for the app running on the phone. It works via Bluetooth with iOS and Android devices and via either USB or Bluetooth to Windows and Mac and any other operating system that includes a screen reader that supports braille. In the USB configuration, Orbit supports both serial and Human Interface Device (HID) protocols, so, if the screen reader supports it, no driver installation is required.

When using it as a stand-alone device, Orbit Reader starts as a reader showing the content of files stored on its SD card. It does not translate the files. The user types in braille or she sends over a translated file from her device. Reader shows the file as it exists; it does not try to interpret it in any way. This means one can send untranslated files, and they show up as computer braille.

There are a number of ways to obtain translated files to store on the card, or one may use a Windows Send To Braille shortcut to translate existing files.

The Reader provides commands to move through a file, mark places, and find text.

In addition to its use as a reader, Orbit Reader lets the user create and edit text. Make no mistake, the Editor is simple and works with only about 15 pages at a time, but again, if one wants complex formatting or spell check, she uses something like Microsoft Word on the PC with Orbit Reader serving as the braille terminal.

Finally, Orbit Reader includes file management capabilities as part of its stand-alone functionality. One can rename and delete files as well as copy and create files and folders.

Braille

The most distinctive feature of Orbit Reader 20 is the braille. Some compare it to signage braille. The dots do not give when the user presses them. Most other refreshable braille displays employ a spring like mechanism that provides a relief point if the dot falls under a load that might cause damage to the hardware. Perceptually, this results in the sensation of pushing the dot down when one applies deliberate force to it. The technology used in the Orbit Reader does not exhibit this characteristic. Once the dot is raised, it is there no matter how hard the user examines it. One may prevent the dots from appearing by deliberately holding them back while refreshing, but it takes a deliberate action, and the intensity factors are adjustable in the device’s software. This unique factor might have implications for beginning braille readers or those who suffer with some degree of neuropathy.

Orbit Reader is made possible by the Transforming Braille Group, LLC, and their goals include dramatically reducing the cost by implementing a breakthrough refreshable braille technology.

The device is not intended to compete with high end PDA type devices. Its purposes include getting braille into the hands of more users.

Parents can afford braille to go with the family tablet, libraries reduce costs for those users that desire electronic distribution, and governments provide inexpensive, easy to maintain devices on which to read.

Transforming Braille Group members can get the device for $320, but this is just the device. Individual member organizations must arrange to package, localize, support, and distribute.

Such packaging might include an SD card, possibly with some content, a USB cable, large print and braille quick start guide, an AC adapter, and a box and packaging to hold it all.

Some of these components vary depending on the location. One might wish to translate the quick start guides into an appropriate language and provide AC adapters compatible with local plugs. There is a utility that lets an organization translate the user interface into any language, so they can deliver the product directly to their customers already configured and preloaded with content on the SD card.

Organizations also want to create software and hardware support systems. While the device is engineered for varying climates, eventually, the battery, at least, needs replacement. It is user replaceable, but some organizations may wish to consider providing such a service.

While no organization has yet published an end user price, it seems fair to assume it will come in between four and five hundred dollars.

So far, CNIB, APH, and RNIB have announced intentions to distribute when the product becomes available this fall.

Compromises

If this all sounds too good to be true, a look at compromises helps explain how it is possible. The first compromise from full featured devices is the lack of cursor routing buttons. If one cannot live without them, this is not the device she wants. What that means to individual users depends on how they use the device. There is no doubt that these buttons associated with each cell make the interface easier on modern operating systems, they got jettisoned in the name of cost savings.

Secondly, the unit refreshes differently from existing technology. It is slower, and one can almost hear the slight tap as each pin rises from left to right, but it does it quickly in about half a second for the whole line–the left side is ready nearly immediately. Again, this refresh rate could be faster with additional cost, but initial indications point to a satisfaction among many users with this alternate technique.

Finally, it is not the smallest device available. It looks good, built ruggedly, and functions well. There is no sleek metal housing on it. One might say the device appears more utilitarian than elegant. It measures about six inches wide, four inches deep, and just over an inch tall. It does not come with a carrying case, but it does contain rings on which one may attach a strap. Some of the well-known case developers, like Executive Products, will probably carry one soon that one may purchase separately.

The important thing to remember about using this device is that there is no translator or file interpretation. What one writes in braille stays in braille. This provides incredible flexibility, because the user may employ any code under any language as long as she and her audience knows how to read it. For notes intended for sighted users, one must either write in computer braille or reverse translate it on the host device. Orbit Reader’s user documentation provides details on obtaining translated files, creating translations, and copying files to the SD card.

If one wants to read a PDF or Word document, she must ether read it with the host device using Orbit Reader as a terminal or convert the file to the braille code of choice and then send it to the SD card. There are usually utilities to help with these tasks, and the user documentation describes some of them.

The Editor is simple. If one intends to write a novel, employing a word processing package on the host device and using Orbit Reader as a terminal is the way to go. The stand-alone editor provides simple editing functions like Find, Mark, Copy, Cut, and Paste.

There is no browser nor even any Wi-Fi on the Orbit Reader. To browse, use the browser on the host device and Orbit Reader as a terminal.

Conclusion

In short, Orbit Reader is not for everyone. It provides a simple, rugged, inexpensive way to bring literacy to more blind people by dramatically reducing the cost of refreshable braille technology.

Back to Assistive Technology