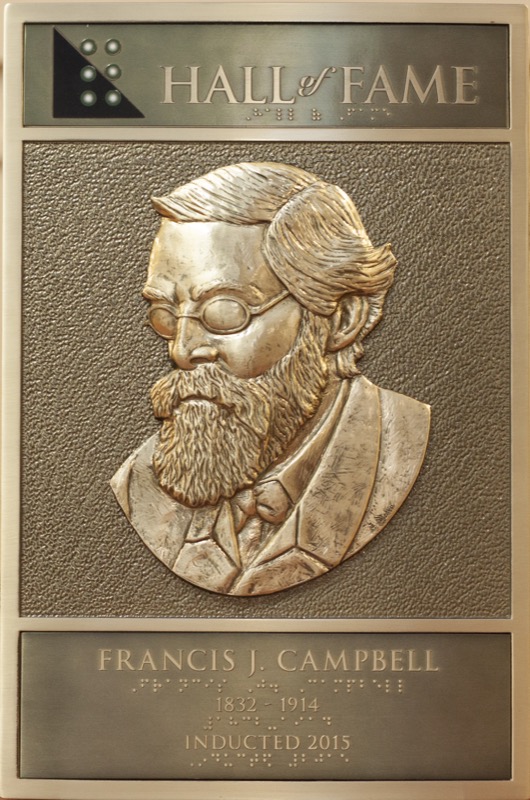

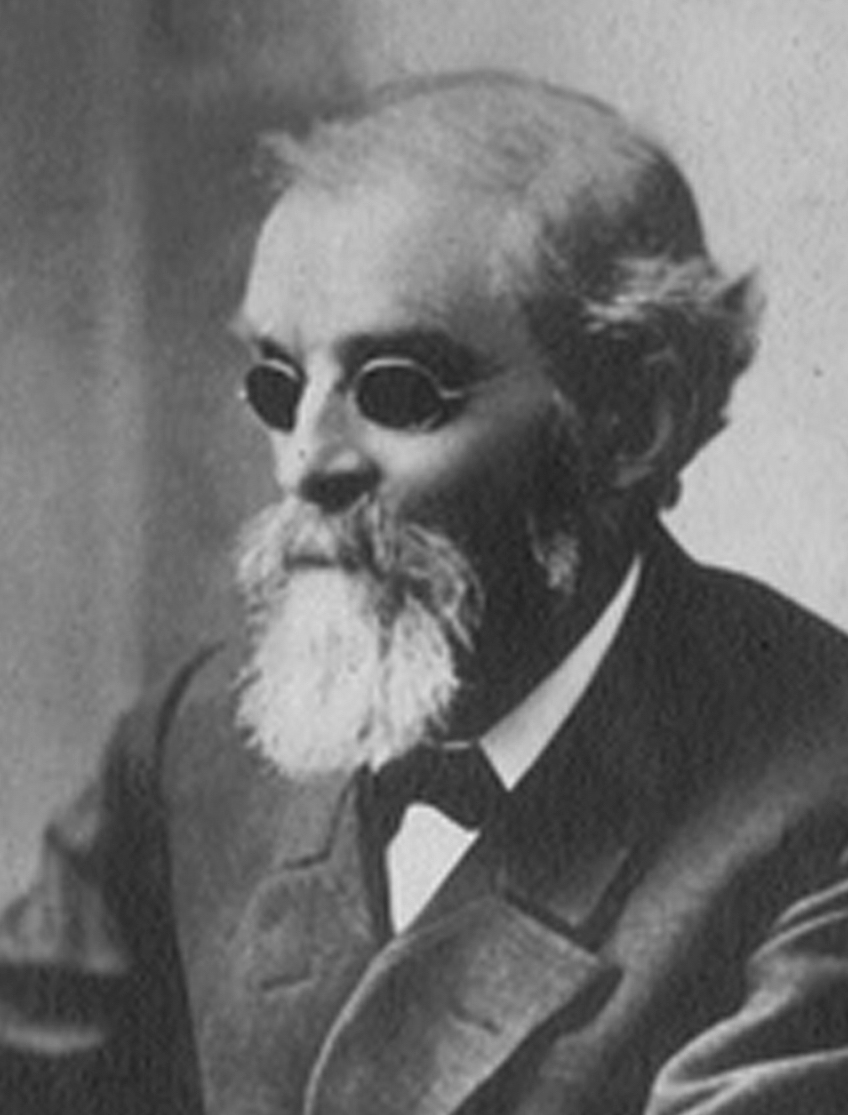

Sir Francis Joseph Campbell

Inducted 2015

Francis Joseph Campbell (1832-1914) was born in the rural mountains of Tennessee in 1832. In 1835, at the age of three and a half, he ran into a thorn bush while playing and subsequently lost his vision.

When someone told him or others who were blind that he or they couldn’t do something, he proved them wrong. Even as a young boy who was blind, he exhibited a strong drive for personal independence. Throughout his life he championed the capabilities of blind people.

He spent his life challenging authority and adamantly advocated that blind people be surrounded by high expectations. He was instrumental in developing school programs whose focus was ensuring that students become independent, employed and self-sufficient.

As a young boy, when his brothers and sisters left their small family farm in the mountains of Tennessee and went off to nearby country school, Francis Campbell, then known as “Little Blind Joseph”, restlessly stayed home because, at that time, blind students were excluded from public schools. He convinced his parents that he needed to go to school and would succeed if he did. His parents found the newly established Tennessee School for the Blind and, at age 12, enrolled him as the schools second enrollee.

At school, when young Francis was told that he did not have the aptitude for music and should pursue a career in basket making, he taught himself to play the piano with the assistance of his willing classmates. He became so musically proficient that at age 18, he was hired to teach music at the school. Later that year he was appointed for a semester as Interim Superintendent after pointing out leadership issues at the School.

After earning his bachelors degree in mathematics from the University of Tennessee, he moved to Massachusetts so his first wife, Mary Bond Campbell, could obtain needed medical care. There he continued his music studies. Later he taught at the Wisconsin School for the Blind. In 1856, as a unrelenting human rights advocate, he voiced very strong anti-slavery views. For teaching a former slave to read, he was threatened that he would be lynched unless he renounced his anti-slavery views. He adamantly refused. He only escaped hanging because of the public sympathy for his blindness.

While in Boston in 1857, he asked Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe if he could observe classes at the Perkins School for the Blind. At the end of the day, Dr. Howe asked Campbell what he thought of his programs. Fully expecting a compliment, he was shocked at Campbells honesty, “Sir, I did not like your programs. Your school is not training your blind students to be independent.”

Taken aback, the shocked Howe invited Campbell for extended discussions wanting to learn how his Perkins programs could improve their effectiveness. Howe, admitting that his programs had significant room for improvement, ultimately hired Campbell to join the Perkins staff.

Campbell told Howe that he would not accept a salary the first year, but if he was successful he would be paid at the sighted teacher rate versus blind teacher scale, which was one half of the former. Campbell in his teaching and his students in their learning were so successful that Howe paid him and, subsequently all blind teachers the same higher rate of pay.

Campbell was the original pioneer and advocate for the expanded core curriculum. To complement the traditional academic program, he insisted upon instruction and maximum participation in rigorous physical activity, vocational training, music, and development of social skills. He taught his students self-determination skills by his example of advocating for himself and expecting them to do the same for themselves.

He “bucked the system” regularly. He pushed Howe to support a program to help Perkins’ graduates find employment at a time when it was highly unusual, if not impossible, for blind people to find jobs. When Howe refused to fund the placement services, Campbell appealed this decision to Perkins Board of Directors. He prevailed over the all-powerful Howe. Thereafter, Perkins graduates were given assistance finding employment. Later, Campbell’s son, Charles, who was previously inducted into the Hall of Fame, extended his father’s influence becoming the first director of the Massachusetts adult vocational services for the blind.

After 11 years at Perkins, Campbell took a sabbatical to Germany but he never returned. He left on good terms with Howe much as was possible after doing the earlier “end run” to the Board. While in Germany, he visited England. He was shocked at the state of education for blind children and adults there. To improve services and expand opportunities for blind people there, he and Dr. T.R. Armitage, established the Royal Normal College (RNC) and Academy of Music for the Blind in 1872. Campbell served as Principal until he retired in 1912. He died in London in 1914 at the age of 63.

Campbell recruited 44 teachers from the United States for his new college. Showing preference for teachers from the U.S. versus England, he stated, “When an American teacher sees a blind child with dirty hands; she shows him how to wash his hands. An English teacher rings for a servant.”

The Royal National College proved so successful that the University of Glasgow awarded him an honorary doctorate. In 1909, King Edward VII conferred knighthood on him in Buckingham Palace with the title “Sir” to precede his name.

Sir Francis developed his own cane techniques and was an accomplished independent traveler. With humor, one writer described that Sir Francis’ cane “had brains, could almost talk, and ought to vote.” The gold handle of Sir Francis’ cane is passed to each successive AER Orientation and Mobility Division Lawrence Blaha Award honoree.

Challenging the system, Campbell improved learning opportunities and ultimately outcomes for blind individuals. Being the first blind person to climb Mt. Blanc in France at age 40, as a role model, he proved that high expectations lead to independence, employment and self-sufficiency for blind people.

He referred to himself as an “American by birth; an Englishman by choice.” Some would advance that his major accomplishments were in Europe. However, clearly he impacted both sides of the Atlantic.

One author described him as “the most famous blind man of his day.” Another referred to him as “The grand old man of the blind who was a keen cyclist, ice skater, oarsman, footballer and mountain climber.”

His spouse, Sophia Faulkner Campbell, wrote of her husband, “His life work was for those who like himself were bereft of sight and he left an example of noble courage and untiring zeal that will ever be an inspiration to the blind.”

Dr. Richard L. Welsh assessed Campbell’s contributions stating, “He has had an influence on the work of our field far beyond what most of us have realized. His approach was based on a realistic understanding of what was capable without vision and on a strong belief in the ability of blind people to function independently. He demonstrated the value of educating the whole child. He understood the need to encourage the development of the physical, intellectual, and emotional sides of each individual. And he appreciated the need for functional life skills that lead to jobs that enabled independence.”

C. Warren Bledsoe summed him up saying “He was the character and personality on which modern work for the blind hinged. After Howe, he was the undoubted champion of the capabilities of blind people, both by his own example, his demands on himself and what he asked of other blind people and society.”

Helen Keller described him and his impact stating, “Wherever he went he started things moving, he always knew what to do, and before the sun of his spirit, obstacles melted away.”

Despite his modest roots, what positive far reaching influence on both sides of the Atlantic he had. His life of stubborn persistence prevailed, fortunately. His absolute non-negotiable belief that blind people are capable and must be independent changed our field.

To think, first known in the rural Tennessee mountains as “Little Blind Joseph,” later his name was changed by an appreciative King of England to “Sir Francis Joseph Campbell.”

Today we say with appreciation, “Thank you, sir!”

Video of the 2015 Induction Ceremony

We apologize for the poor audio.