Sir Charles Frederick Fraser

Inducted 2016

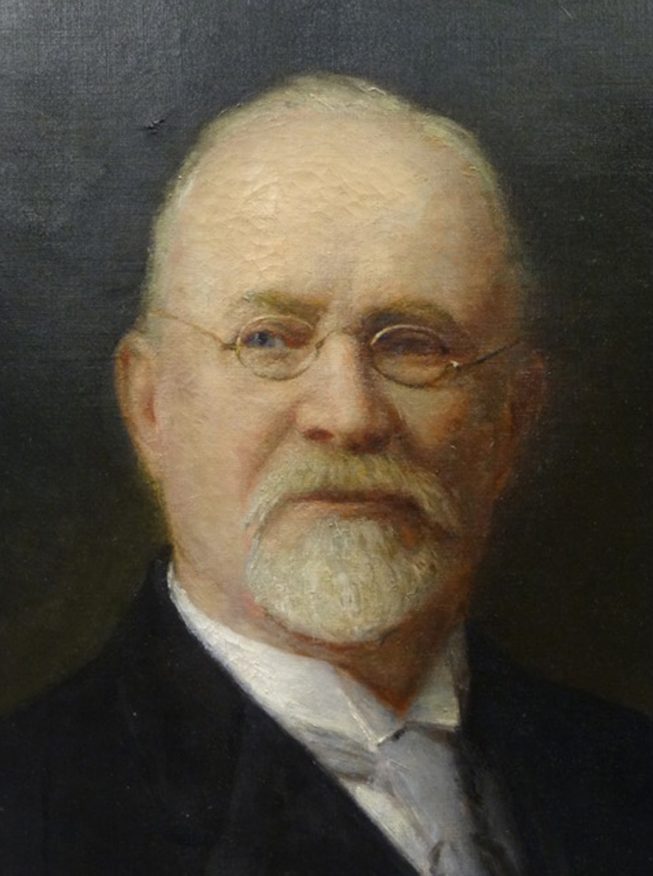

Portrait of Sir Charles Frederick Fraser.

Charles Frederick Fraser (1850–1925) was born in the small town of Windsor, Nova Scotia, Canada. At the age of seven he injured his eye with a pocketknife while whittling. Despite treatment from his father, a physician, and a renowned eye specialist in Boston the vision in his injured eye could not be saved. Shortly thereafter the vision in his other eye began to fail and by the age of 13, after completing his elementary schooling in Windsor, he was enrolled at the Perkins Asylum for the Blind near Boston.

Reported to be a clever but headstrong student, Fraser believed that those who were blind should be self-sufficient and active members of society. After completing his education at Perkins, he returned to Nova Scotia to pursue a career in business. Just one year later at the age of twenty-two he became the first Superintendent of the Halifax Asylum for the Blind. This institution had opened two years earlier in 1871 and had fewer than ten students. Under Sir Fredrick’s guidance the paradigm of the Asylum shifted from being a charitable institution for the blind to being an educational facility preparing students to take their place in the world. When Fraser retired fifty years later in 1923, the Halifax School for the Blind was renowned for its accomplished graduates and innovative programs with enrollments averaging 120 students per year.

Fraser faced many challenges during his first few years as superintendent. There were known to be many school-aged children who were blind residing in the province, but educating these children was generally believed to be unnecessary. Fraser travelled throughout Atlantic Canada meeting with families, community leaders, and government representatives to convince them of the critical importance of educating youth who were blind. Nova Scotia, one of the four founding provinces of Canadian Confederation in 1867, was composed of a vast geographic area with a population of only 65,000 spread across hundreds of miles. Other nearby provinces (Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick), were even more rural and sparsely populated. Newfoundland, a colony of England until 1949, was only accessible by sea. Yet, Fraser was able to convince parents and colonial governments to have their children who were blind educated in Halifax and to contribute to the costs of such an education. Through compelling and committed leadership, Fraser helped families and governments recognize both the abilities and rights of the blind and society’s responsibility to assist with their realization.

As superintendent, Fraser had a multitude of duties. He provided the leadership and supervision generally required in residential schools. In his typically innovative fashion, Fraser gave preference to hiring teachers who were blind, thus providing successful adult role models for both students and their families. In addition to his administrative duties, for forty-two hours a week Fraser taught an array of academic subjects, music and chair caning. Providing a comprehensive curriculum was critical for Fraser. Students were challenged to master academic subjects, take mobility training, participate in recreational activities, study music, and learn skills to be used in procuring employment upon graduation. Every summer he travelled on behalf of the school giving public lectures. He was accompanied by students who gave concerts and demonstrated skills acquired at the School. Significant monies were raised to create an Endowment Fund for the support of worthy projects for the blind, the purchase of new musical instruments for the school, and additions to teaching supplies. During Fraser’s fifty years of work and leadership, the school flourished; new classrooms and residents were built and hundreds of children were educated and prepared for employment and independent living.

Fraser was an ardent lobbyist and instigated frequent interactions with political and educational personnel. Due to Fraser’s tireless efforts and dedication, the Halifax School for the Blind became a center of advocacy as he campaigned for supports for both the School and for all citizens of the Atlantic Provinces who were blind. By the end of the1880s, Fraser had secured free education for students who were blind, created a circulating library of Braille books, established an outreach program for preschool children and those needing to prepare for attendance at the School, created the Home Teaching Society for the Blind to provide instruction to adults who were blind, established a fund to support School for the Blind graduates beginning careers or further training, contributed to the establishment of a Canadian Printing House for the Blind, and convinced the Post Office of Canada to provide free delivery for Braille books. In 1909 he helped to found the Maritime Association for the blind that focused on promoting the employment of blind adults. In 1911, following Fraser’s campaign to prevent blindness, the Nova Scotia government legislated medical personnel to prophylactically treat all newborns for ophthalmia neonatorum, a common and preventable cause of childhood blindness.

Dedication, innovation and collaboration are hallmarks of Fraser’s career. These important skills helped him to support the formation of many organizations for the blind in Canada that remain influential today including the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. Fraser’s talents in this area were wide reaching and he was frequently invited to present at national and international conferences as well as acting as a consultant to both the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind and the province of Ontario.

Fraser was also a successful businessman and volunteer. He edited The Critic, a weekly literary and commercial journal; was a member and served on the executive of the North British Society, the Halifax Archaeological Institute, and the Halifax Canadian Club; and supported the Nova Scotia League for the Care and Protection of Feeble-minded Persons. He pursued his initial interest in business by serving as president of a number of companies including the Nova Scotia Telephone and Trinidad Consolidated Telephone Company and as a director of a number of firms including Eastern Trust and Empire Trust.

It is not surprising that Charles Frederick Fraser received many accolades and honors during his years of dedication and service. These included three honorary degrees, special recognition from the Nova Scotia legislature and numerous local benefactor awards. In 1915, in recognition for his life’s work in the field of blindness, Charles Frederick Fraser was knighted by King George V of England.

For fifty years, Sir Frederick Fraser continued his commitment to providing exemplary programs and services for those who were blind. Perhaps the final six years of his career were the most challenging. In 1917, during World War I, a horrendous explosion occurred after an ammunition ship collided with another ship in Halifax harbor. Two thousand people were instantly killed and most buildings in the city were leveled. Thousands of survivors suffered serious eye injuries with many being totally blinded by glass and shrapnel from the explosion. The School for the Blind, somewhat protected by its location to the south of Citadel Hill, suffered significant structural damage including every window being blown out. After forty-four years of tireless labor, Fraser would have to rebuild a significant number of the school’s structures and revive numerous programs and services in a city reeling from the damage and loss of life caused by the largest man made explosion to date in the history of the world. He immediately set to work repairing sections of the school to allow for the diagnosis and care of those blinded by the explosion. To facilitate this, children enrolled in the school at the time were returned home to their families. It took several years, but before his retirement in 1923, Sir Frederick Fraser had successfully orchestrated the full return of programs and services to blind children of Atlantic Canada. He died two years later in 1925.

In 1984, the Atlantic Provinces Special Education Authority built a Resource Centre to serve the educational needs of children and youth who are visually impaired. This replaced and expanded the role of the former Halifax School for the Blind. However, the pioneering work of Sir Fredrick Fraser, a profoundly dedicated, innovative and determined educator was the foundation for many of the programs and services being offered and so it seemed only fitting that the school building of the Resource Center be named “Sir Frederick Fraser School.”

Sir Frederick Fraser’s extensive accomplishments have positively influenced the lives of thousands of individuals who are visually impaired in Atlantic Canada over the last century, and continue to do so today. For this reason he is truly deserving of induction into The Hall of Fame for Leaders and Legends and will always be remembered as both a leader and a legend for those who are blind in Canada.