Alice Raftary: Hall of Fame Interview

Interviewed by Michael Bina, January 2014

1. When you were growing up what career did you think you would pursue?

In elementary school, I thought I would like to be a plumber and work with my father. At thirteen, I decided I would like to be a discalced Carmelite nun. But at seventeen, I decided on a career in chemical research in the field of nutrition. At Marygrove College, I received a Bachelors degree in liberal arts (BS), specializing in science. Alas, I fell in love with Raymond during my senior year and my career choice became marriage, wife and mother; Ray and I would raise wonderful children and in my spare time I would study philosophy, music and art.

The career moved along splendidly, but shortly after our tenth anniversary, as I expected our eighth child, I became legally blind. I was told my eye disease would not lead to total blindness. I began Braille lessons. Legal blindness did not seem so bad until I was told the disease was hereditary. The doctors suggested that half of my children would become blind, and that one of my little boys was probably already legally blind. That little boy was skipping, happily, down the hall holding a doctor’s hand. A moment of terror gripped me. The scene is like a photograph in my memory. My heart stopped. It is hard to describe the pain of that terrible moment. Then determination came to me and I knew that I would do something that would insure that none of my children would ever think that blindness must ruin their lives.

2. Did you ever imagine that you would be working in the field of blindness? Did you find the field or did it find you?

Edna Fink, a consulting teacher for preschool blind children in Detroit, came to teach me Braille and opened my eyes to a new career field. I consulted the State Rehabilitation Services. I received an education grant. It took four years to complete, usually only taking one class at a time. When I received my Masters Degree in Education in 1969, my children were all in full-time school. I could enter employment.

3. Who or what influenced you to work in this field?

I had interned at Greater Detroit Society for the Blind (now known as the Greater Detroit Agency for the Blind and Visually Impaired) and my supervisor, Gerald DeAngeles, had a special love for work with deaf-blind people. I showed an aptitude in this area and was hired as a part-time specialist.

By the end of a year of part time employment, I was exhausted as I tried to maintain my homemaking in the same style as I did before. Ray and I decided on a change in our lifestyle. I would work full-time and be eligible for the agency’s health insurance for my whole family. My husband was self-employed and his time was flexible. Ray took over relations with the school system and he saw the children off to school in the morning making sure they wore their snow boots, etc. My oldest daughter, Mary, who was a sophomore in high school, arrived home before our elementary school children and she would start dinner. The marriage career continued wonderfully and now I had added to it an exciting new career in the blindness field.

4. Do you still recall the names of some of your blind or low vision students and clients? Which three come to mind and why?

I remember many client cases and I tell their stories often. It’s difficult to choose among them.

Ethel Greenwald had been a teacher until neurological disease caused her to be a totally blind paraplegic. I worked with her transition from rehab center to her home. I never met her husband, but she said he liked her cooking and she kept a kosher kitchen. She was a wonderful woman. It wasn’t long before she became one of my volunteers. She taught Braille to one carefully chosen student at a time. Her attitude inspired them and me too as she said, “I keep myself so busy doing the things I can do, that I don’t have time to fret about the things I can’t do.”

Joan Jeffer became totally blind overnight from the herpes virus. She went to bed, where she stayed for 6 months. She said, “When you’re in bed, it’s supposed to be dark, and that’s how I kept my sanity.” After 6 months she finally came down to the living room and sat on the couch while her family waited for her there and nagged her to get a teacher for the blind. She finally gave in to her family’s nagging to have a rehabilitation teacher by saying, “You get someone to teach me to iron by husband’s shirts and I’ll take lessons.” When I arrived at Mrs. Jeffer’s house, an ironing board had been set up in the living room with the iron and a dampened white dress shirt with starched collar and cuffs. To watch this lesson with her were her mother, her daughter and her next-door neighbor. I asked Mrs. Jeffer if she ever watched television while she did her ironing. Indeed she had. It was not a difficult lesson as I showed her how to feel up the cord to the iron handle and encouraged her as she took her steps through smoothing and ironing the shirt collar, etc. I had turned the temperature of the iron down just a little, as I knew she’d be slow and she did a creditable job. She was an intelligent woman, had been a fine housekeeper and learned quickly to restore her position as a stellar homemaker.

A couple years later, I received a call from my cousin who said she knew I worked with blind people. She wanted to tell me about her wonderful blind friend. She and her husband had been to dinner the night before and she wanted to tell me about the friend who was a wonderful housekeeper and a great cook. As she talked, I thought I recognized her friend and, indeed, it was Mrs. Jeffer.

Mrs. Bart was assigned to me as an emergency case. She was a totally blind diabetic who had attempted suicide. She had been hospitalized in the psychiatric unit for three months. She returned home, and two weeks later attempted suicide again. This time she was only hospitalized for two weeks because, as she said, “I knew the answers they wanted.” I asked what had brought her to this desperate action. She said, “My granddaughter comes every week to do my laundry and it makes me crazy. I gave her a long laundry lesson. The next week when I asked how the week had gone, she said, “Not bad.” I asked about her laundry. “Oh, my grand daughter did it for me yesterday.” I was deflated. Had she forgotten the lesson? “No, my dear. She did it, but I told her how.”

At our last lesson she said, “I believe suicide is wrong. I have always believed suicide is wrong, but I always ran everything—my house, my family and my life. When I lost my sight it seemed like the only sensible thing to do. But, now I know I can control my life.”

Awhile later, I met Mrs. Bart’s roomer on the street one day and he asked me if I thought the, “old lady was still blind?” Yes she was totally blind. He said, “I don’t think so. She used to open her purse and tell me to take out what I needed to get her a loaf of bread. Now she counts her money.” Mrs. Bart had taken charge!

Sophie Agardy was an attractive middle-aged deaf woman. She and her husband were socially active in the deaf community. One of her hobbies was an intricate form of embroidery, which only appears on the top surface of the linen. As her vision had diminished she kept up most of her homemaking skills, but she realized a time had come for her to learn Braille. She approached instruction with her usual, practical intensity. I gave her two lessons in two weeks and she was into reading books and magazines. Mrs. Agardy loved to travel and when the personnel at the airport wanted her to use a wheel chair, she told them, in a no nonsense way, through her interpreter “I’m not handicapped, I just can’t see or hear.” What a woman!

I learned a great lesson in the depths of depression suffered by newly blinded persons and of the importance of learning to control one’s life.

5. What would you list as your two or three proudest moments in your career?

My Hall of Fame induction was certainly a highlight.

When a client’s wife told my sister, “The day you brought Alice to our house, was the most important day of our life.” Warmth from a compliment like that never cools.

Lecturing at the Physicians Education Seminar at University of Michigan was a pretty heady experience.

When a senior citizen, at a fundraising session, said, “Yes, Mrs. Raftary was my teacher, but after I learned, I had to do for myself.” Oh, I was proud of him! You see, we teach and counsel, but the blind person really rehabilitates himself.

When Ethel Greenwald told me what her Braille student said, “For ten years, I tried to sleep as much as I could because the days were so intolerably long, but since Mrs. Raftary has been teaching me the days aren’t long enough.” Those words made my heart leap for joy!

Every success, large or small, was a proud moment in my career.

6. Did you ever imagine that you would be recognized and inducted in the field’s Hall of Fame? When you were informed that you were an inductee, what were your thoughts?

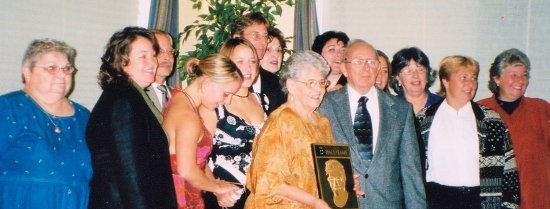

No, I never expected such an honor. I am still humbled by it. It was like a miracle of good fortune. My friends and family were all excited about the honor. Thirteen of them came with me to cheer at my induction.

7. During your career you undoubtedly saw the field change in many different ways. How did it change? In which ways do you wish would have changed more?

There has been a great surge in work with the elderly. New programs and service patterns have been developed all over the country. That’s a very good thing.

The impact of technology is stunning in its affect on the lives of persons with vision impairment. It has brought new instructional areas of teaching to specialists in the blindness field. As a matter of fact, I sometimes worry if enthusiasm for new technology has diminished the importance of basic daily living skills.

Deaf professionals have become active in rehabilitation of deaf-blind youth and adults. The center for deaf-blind youth and adults is thriving.

8. What three to five pieces of advice would you give to people entering the field just beginning their first experience working with clients or students?

Pay attention to your clients and students so that you gain a greater understanding of the human mind and heart. There are wonderful things to learn.

I tell teachers: No matter how much paperwork you have to do on your initial client contact, be sure that you have established yourself as a TEACHER by teaching the client something. This should be something that is simple/easy and significant to him/her. Ex: Writing signature, identifying coins, folding money, etc.

When you attend conferences, do not sit and lunch with your buddies. Meet people from other agencies and states to learn about new techniques and service patterns.

Address your clients formally. Never assume the use of first names for your client or for yourself. If you present yourself as Betty or Tommy, you diminish your professional status. If you address the client by his or her first name, you demean their dignity as adults.

9. What are three to five pieces of advice would you give to those in the field who are experienced in the field?

Invest your time and some money into the growth of your profession. Join and be active in your professional associations (AERBVI, MACRT), go to conferences, etc.

Continue to learn new techniques and new systems.

Share your expertise.

Mentor others in the field and encourage others to work in the field of blindness.

10. When you look back on your career, what was a humorous experience that really made you laugh?

“Funny” is a funny thing. I told this story on myself in a rehab counseling class. I was fiddling with a metal stand near the wall and my husband asked me what I was doing. I was trying to get a drink. “That’s not a drinking fountain. It’s an ash tray.” A blind man in the class laughed so hard he almost fell off his chair. A woman at the other end of the table burst into tears. The story broke her heart. She felt so sorry for me.

Maybe a better story:

When I was out visiting my sister in Oklahoma, she asked me if I would go and visit a friend with her. Her friend’s husband had become totally blind from glaucoma and he was so bitter and angry he refused to even get his own glass of water. His wife was at wit’s end. The man wasn’t interested in any thing I suggested he try, but I finally went all out to get him to try to write his signature. Even though he was resistant we got the tables up to him and I put paper and pencil in his hand and said, “Just close your eyes and give me an autograph any place on the piece of paper.” He did. Then I handed the paper to my sister and I said, “Can you read this?” She said, “Oh, yes,” and he said, “Huh! Yeah, you know my name.” I said, “That’s right.” I turned the paper over and I said, “Now write on here anything you want to write. Just write it quickly across the paper.” He kind of gritted his teeth and he wrote and I took the paper and handed it to his wife and I said, “Can you read this?” She smiled and said, “Oh, yes.” Then she stopped and I asked, “What does it say?” “It says, Go to hell.”

There it was, straight from the heart. He reached across the table to me and the look on his face was that of a person who had just witnessed a miracle and he said to me, “What was that you were saying about money?” That was a funny jump into rehabilitation.

11. What question haven’t I asked that you wish I had?

About myself, I would add that I have had a life of incredible good fortune. Who would have thought that vision loss would be such a blessing for me, my family, and the hundreds of visually impaired people I have known throughout my career?

I am practical and pragmatic and often oversimplify. I always try to make things uncomplicated and easy. I like them that way because I’m a little bit lazy. I love to watch the success of teachers/therapists and clients. I gladly teach someone a technique so that they are able to do the arduous work of prolonged instruction or training.

I have been retired for over twenty years, I’m still active in AERBVI(Michigan Chapter) and MACRT. I give speeches occasionally and I read and talk about blindness to school children. And, I have lots of fun. My family continues to grow with my tenth great grandchild due on my birthday.

Photos: Alice Raftary in the garden, January 2014; Presenting to lower elementary students; Parasailing over the Straits of Mackinac in 2010; Presenting at MACRT in 2012; The 13 family members and friends who traveled to Louisville to cheer for Alice at the Hall of Fame induction ceremony.